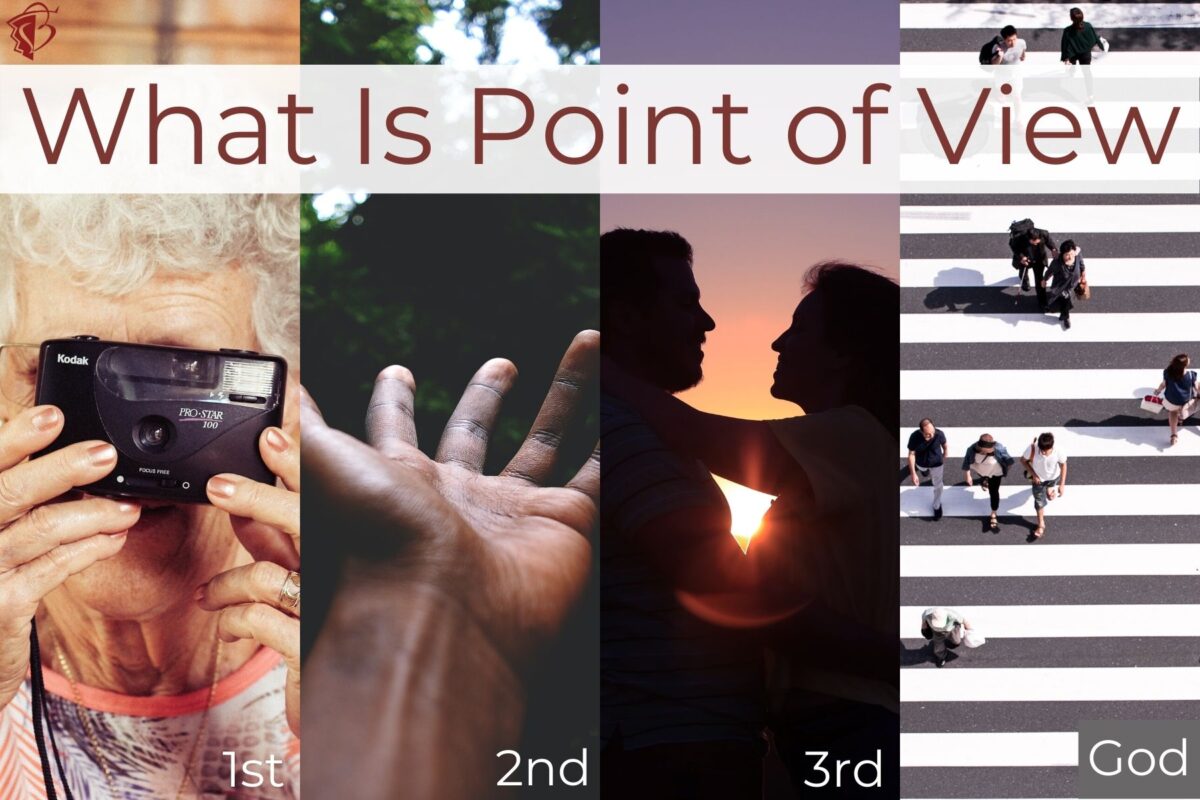

When someone refers to point of view in writing, they are referring to the lens through which the story is told. This encompasses everything from who is telling the story to who the villain is to how close the reader feels to the characters and events. By choosing the right lens, an author can effectively control the release of information to craft a thrilling tale and, to a degree, control which characters readers root for. There are four types of point of view, and they each have pros and cons.

First person point of view

First person is tied with third person for the most popular point of view today. When a story is in first person, a character speaks directly to the reader to tell their story, so authors use “I,” “we,” “my,” and “our” pronouns when writing first person. Here’s an example of first person from Laird Hunt’s novel Neverhome:

I wanted to take up the dead man’s head and cradle it but I did not do that and knew that that kind of a thought was another thing I was going to have to learn to kill. Some of them on relief teased me a little as I sat there my minute but I didn’t pay them any mind. They hadn’t killed anyone that morning (19).

In this excerpt, the protagonist tells her own story instead of the author telling her story. First person point of view allows the character’s voice to shine. That’s why this example doesn’t use perfect grammar or sentence composition. The speaking character is a farm girl turned soldier in the Civil War. She doesn’t have the same linguistic skills as the author, so Hunt is limited to her vocabulary and composition skills.

Because first person is told directly through the eyes (and other senses) of a character, it is a close point of view. Close means readers get to see what the character is thinking and feeling as well as what they’re doing. They feel like they really know the character. They feel close to them.

Third person point of view

Third person is the other point of view popular with contemporary readers and writers. In third person, the author is the one telling the story, not a character, so the author uses “he,” “she,” and “they” pronouns. Here’s an example from Laurence MacNaughton’s novel It Happened One Doomsday:

In the spirit of being prepared, Dru kept a flashlight under the cash register. But in the case of magical sparks and red glowing eyes, she needed something stronger. She reached for a crystal (15).

This story is still in Dru’s point of view because it focuses on her and only reveals her internal thoughts and emotions, but she is not telling her story directly to the reader. Instead, the author is telling her story. In third person, MacNaughton isn’t limited by his character’s vocabulary and composition skills, so he can use all the writing skills and tricks he’s gathered and more of his authorial voice to write Dru’s tale.

Third person point of view can be close or distant. When the author chooses to reveal the main character’s thoughts and feeling a lot, third person can be almost as close as first person. However, if the author chooses to only reveal the main character’s internal life occasionally, readers don’t feel as close to the character, so the point of view is distant.

Omniscient point of view

Omniscient point of view is also known as the god perspective or the all-knowing perspective. Unlike first and third person, omniscient shows more than one character’s thoughts and feelings at a time. All the other points of view need to switch point of view character, the person whose internal thoughts and feelings they show, between scenes or chapters. Omniscient can show different characters’ internal life whenever the author chooses. When done well, this can expand the reader’s understanding of the story and character relationships. When done poorly, readers become confused. Stephen King often uses omniscient. Here’s an example from Carrie:

No one was really surprised when it happened, not really, not on the subconscious level where savage things grow. On the surface all of the girls in the shower room were shocked, thrilled, ashamed, or simply glad that the White bitch had taken it in the mouth again (3-4).

In the excerpt, the author reveals what all the high school girls in the town thought, making this omniscient point of view. Like third person, omniscient uses “he,” “she,” and “they” pronouns because the author is the one revealing the story, not the characters. If King had wanted to, he could have written “On the surface they were shocked . . .” instead of using “all of the girls.”

Omniscient is the most distant of all the points of view. Because diving into different characters’ heads too frequently is confusing, the reader doesn’t get many internal thoughts and feelings from any character. This means they don’t get to know the characters as intimately as they do in any other point of view.

Along with second person, omniscient is one of the most difficult points of view to pull off. Not only is it confusing when the author jumps back and forth between characters’ heads, it can also be difficult for readers to know which character is the protagonist. The story can lack a focal point, and it’s easier for authors to go off on tangents. Using multiple points of view can be an effective alternative to omniscient. This is where the author uses first, second, or third person but alternates the point of view character every scene, chapter, or section.

Second person point of view

Authors use “you” and “your” pronouns in second person, making the reader the point of view character. This means they are telling the reader what to do and think to a point. People don’t like to be told this, so second person is tricky to pull off. However, when done well, second person allows readers to truly experience another person’s life for a moment. That’s Lorrie Moore’s goal in her short story collection Self Help. Here’s an example of second person from her story “How:”

Begin by meeting him in a class, in a bar, at a rummage sale. Maybe he teaches sixth grade. Manages a hardware store. Foreman at a carton factory. He will be a good dancer. He will have perfectly cut hair. He will laugh at your jokes (55).

One way Moore addresses readers not liking to be told what to do in her second person stories is by giving the reader some options – how they meet the man – and telling readers everything else.

Second person is close. Even though the author might not reveal as many internal thoughts and feelings as they would had they chosen first or third person, it is still close. The reader will fill in any missing internal thoughts with their own.

The lens of your story

A final, essential component of point of view is which character the author chooses to focus on. Usually, the character who is in the middle of or is the most affected by the events of the story is the most interesting one to read about because they have the largest character arc. Most people avoid conflict in their daily lives. Most readers want to experience that avoided conflict through the safety of a book. Choose the character with conflict to be the lens for your story, then choose the best point of view for your tale and character to Ignite Your Ink.

(Stay tuned for POV 2: How to Choose Point of View.)

Image courtesy of unsplash.com

Terrific article, Caitlin. Looking forward to POV 2!

Thank you, Stacy!

I love your examples of the various POVs. Thanks!

Thank you, Laurel!